Music Market Focus: Japan [Latest Stats, Trends, & Analysis]

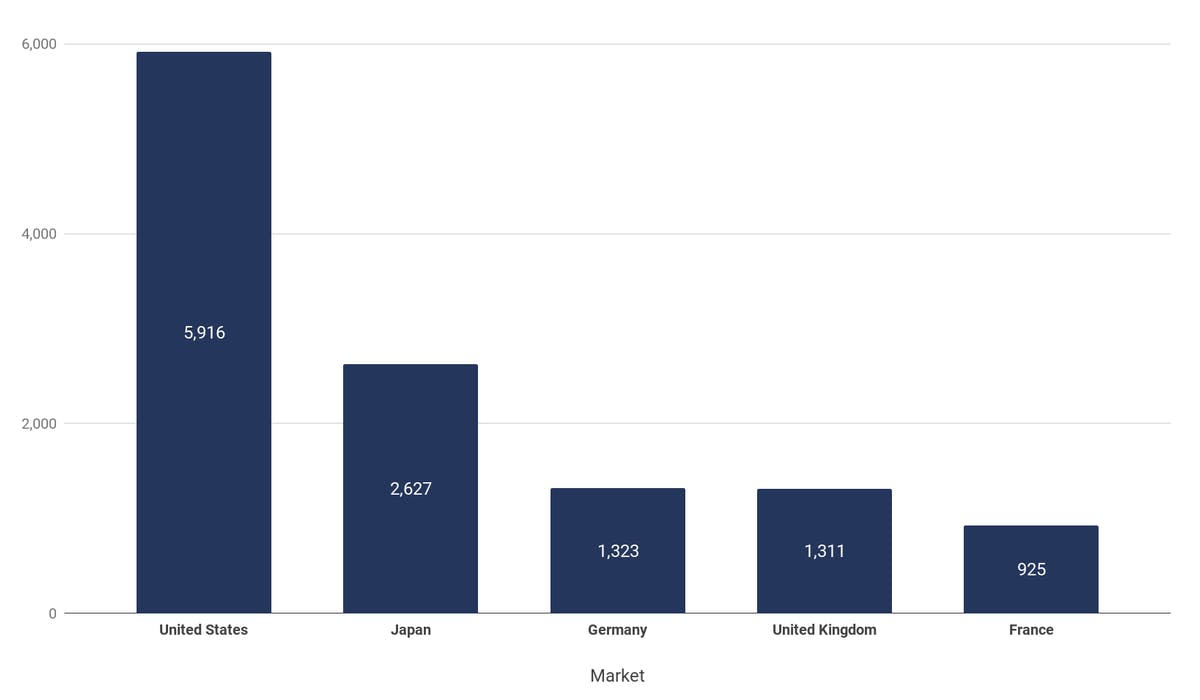

Despite the fact that Japan is the second largest music market (which is actually not that surprising for a country with

the 3rd GDP worldwide and a population of 127 million), it remains one of the most misunderstood and challenging local

industries in the world. That is for a good reason. With its unique cultural patterns and their effect on the market

structure, Japan is very different from the Western markets.

Just a quick sidetone, before we get into it: If you're interested in a more first-hand insights into the Japanese

market, check out our interview with Goshi Manabe, one of the leading experts on the local music business, who's spent

the last 20 years building the bridge between Japanese music industry and the rest of the world.

Structure of the Japanese Music Industry

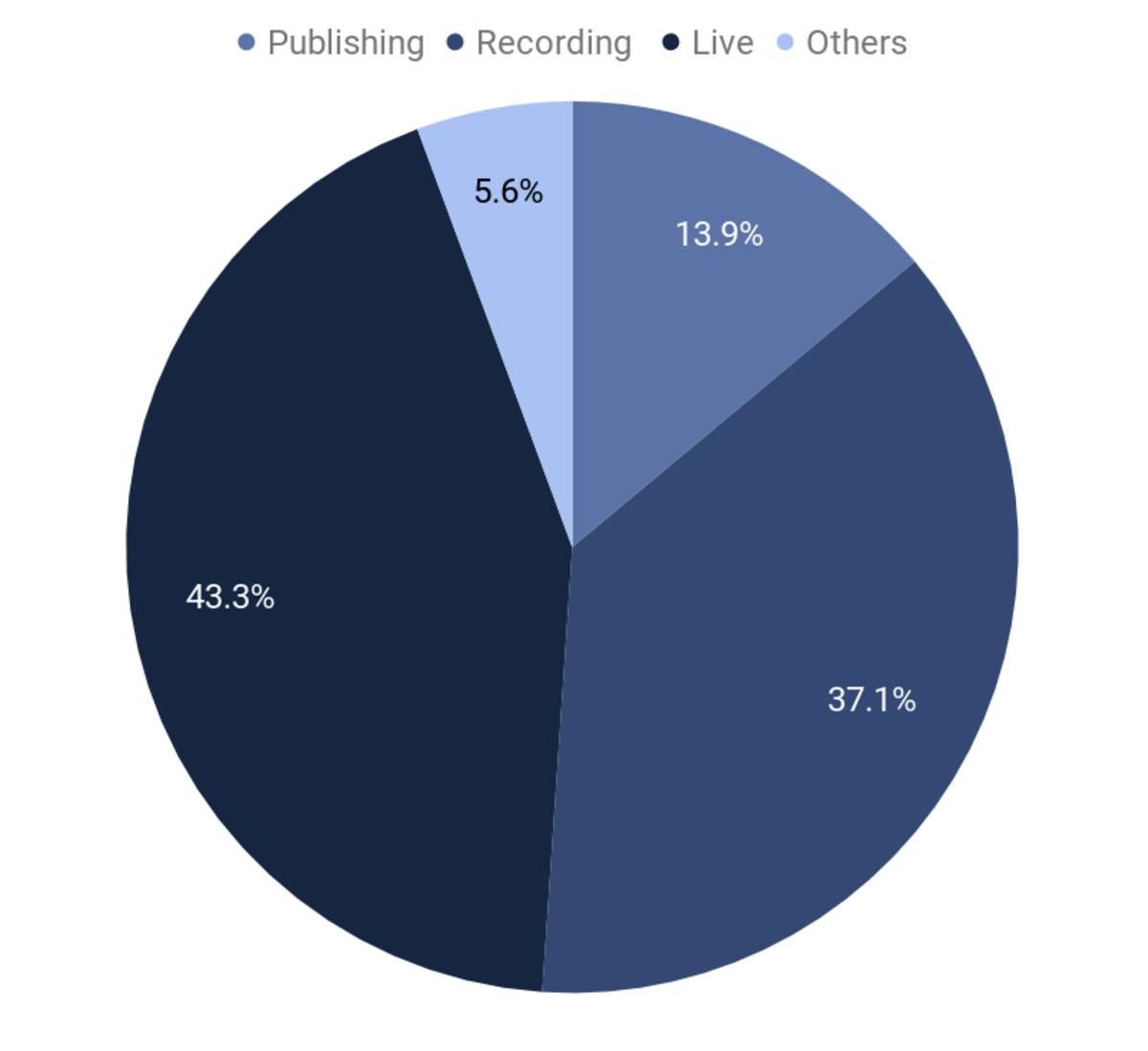

Total revenues of the music industry are estimated at $7 billion, generated by 3 main sub-industries: live, recording and publishing. Over 90% of all live and recording revenues come from domestic acts, while publishing is considered the most foreigner-friendly part of the industry with 20-25% of revenues generated by international artists.

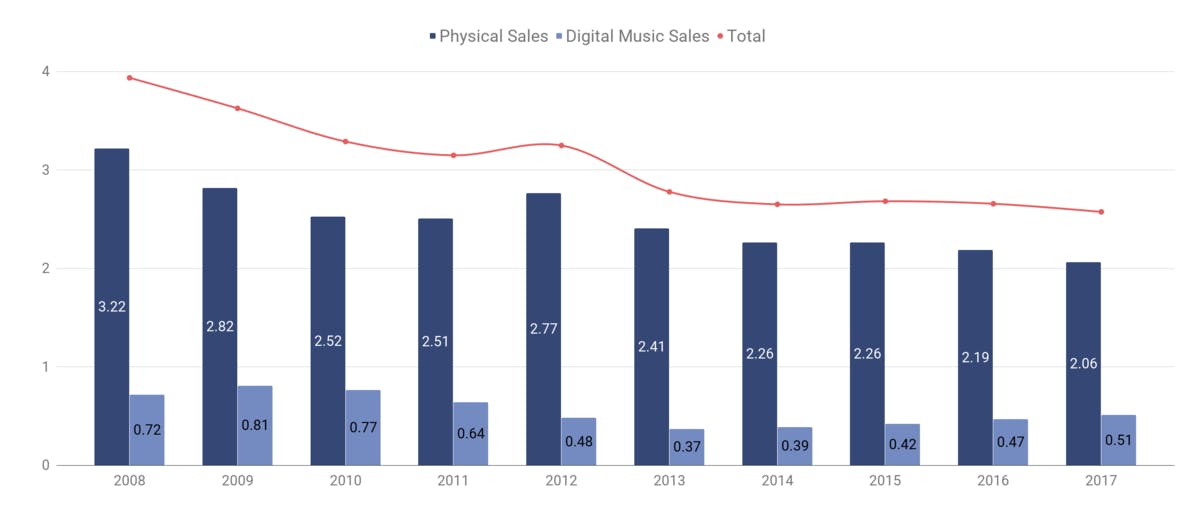

Japan's Recording Industry Explored

The recording industry in Japan is actually facing a big challenge: physical sales have been declining for the last 8

years, and recent growth of the digital formats can't offset that drop yet. Despite the availability of all global

streaming services and a number of local solutions like RecoChoku, LINE Music and AWA, streaming still fails to

penetrate Japan the way it did with the most of western markets. That leaves Japan in a lingering transition phase.

As of February 2019, only 3 songs out of the top-10 of Billboard Japan Hot 100 were actually available on Spotify. Lack

of local content on the platform means that potential customers can’t see the value of the service. As a result,

streaming services can't get enough traction to convince labels to make their catalogs available for streaming and the

cycle goes on, creating an endless catch-22 loop. The problem can definitely be resolved, as some of the biggest local

right-holders are slowly changing their mind (or even introducing their own streaming services).

In the end, streaming is the only real answer to the decline of the physical market in Japan. The recent numbers,

published by RIAJ, show noticeable growth of the streaming market over the course of 2018, as the audio-subscription and

ad-supported video streaming revenues are up 30% and 62% accordingly. Overtaking the digital downloads as the main

revenue source in the digital space for the first time in the market history, streaming shows a big promise – though it

is still a long way to go until the new distribution models can really challenge the reign of the physical formats.

While not impacting the revenue structure directly, streaming has already revolutionized music consumption. According to the RIAA study, conducted in 2016 the most popular way to listen to music in Japan is actually a streaming platform – 42,7% of respondents employed YouTube as the primary source for music discovery and consumption. The popularity of VOD also affects the importance of traditional channels. Radio in Japan is now focusing more and more on the talk format, rather than music broadcasts, and it shows – based on the aforementioned RIAJ study, less than 10% of respondents used radio, including digital broadcasts, as a source of music. Therefore, on-demand video content is probably the channel to focus on for international artists trying to make it in Japan.

Six-story Karaoke Kan in Japan

Another particular phenomenon of the Japanese market is the popularity of Karaoke. It is the favourite pastime in Japan and a huge industry, generating over $5 billions in 2017. While Karaoke revenues themselves are not included in the music industry numbers, performance rights fees generated by Karaoke bars compose a substantial part of the publishing business, which means that a Karaoke-hit can become a gold mine for the artist. Yet, as most of the Japanese don’t feel comfortable singing in foreign languages, this path remains mostly closed for international acts.

What Makes Japan’s Music Industry Unique?

While the statistics mentioned above allow to draw a general picture of the market, to understand exactly why the Japanese industry is different from the western ones we will now take a deeper look at the drivers of the industry, exploring unique cultural patterns of the Japanese market.

Fan-culture in Japan

Japan is notorious for having very passionate music fans. The fan engagement phenomenon is deeply rooted in the Japanese

collectivistic, but highly competitive culture. Japanese fan often strive to be the biggest fan there is: feeling bad

for not getting the limited edition release of their favourite idol's latest single, waiting in a line for hours at the

meet & greet sessions, spending Friday evening at the Karaoke Bar with the friends from the fan-club and attaching great

value to their relationships with the artist – it is not uncommon, for instance, for Japanese artists to get monetary

donations in their fan mail, even though they never explicitly asked for it.

This is yet another reason for the limited success of the streaming services in Japan – their "all you can eat" approach

just doesn't seem to fit well with the fans who want to support specific artists. Same goes for the rest of the Japanese

industry, orchestrated by the fan culture: from the artist-related collectibles to the relentlessness of CD, it all

seems to lead back to the needs and desires of the fans.

The Idol System

The second fundamental concept of the industry is Japan’s take on the mainstream music industry and the idol system. A

vast majority of the mainstream acts in Japan are signed to management companies, such as AKS, Johnny & Associates and

Amuse Inc. Such management companies operate on the basis of strict employer-employee relationships, meaning that when

the artist signs a deal with the company, they become a regular employee, giving up all control over their public

figure. That means that music executives have an unseen level of control over the artists, able to dictate their every

decision, from their appearance to their love life. A contractual ban on romantic relationships, for example, is very

common amongst the idols. That unique environment is the essence of the idol system.

The idol system is widespread across East Asia, and you can't talk about the region without mentioning South Korea – 6th

largest music market in the world. Despite the political tensions between Japan and Korea, cultural diffusion has made

the markets very similar. Yet there is one notable difference between their approach: while Japanese artists are focused

on the domestic market, their Korean counterparts are open to global opportunities. And, naturally, Japan becomes the

first priority for the Korean acts: practically all big K-pop artists record two versions of their songs – one in Korean

and one in Japanese, allowing them to go head-to-head with the local artists.

The idol system opens up unique possibilities when it comes to optimizing the star-production process. Some of the

idol-bands are run by the management companies to create a continuous flow of new faces, serving as accelerators

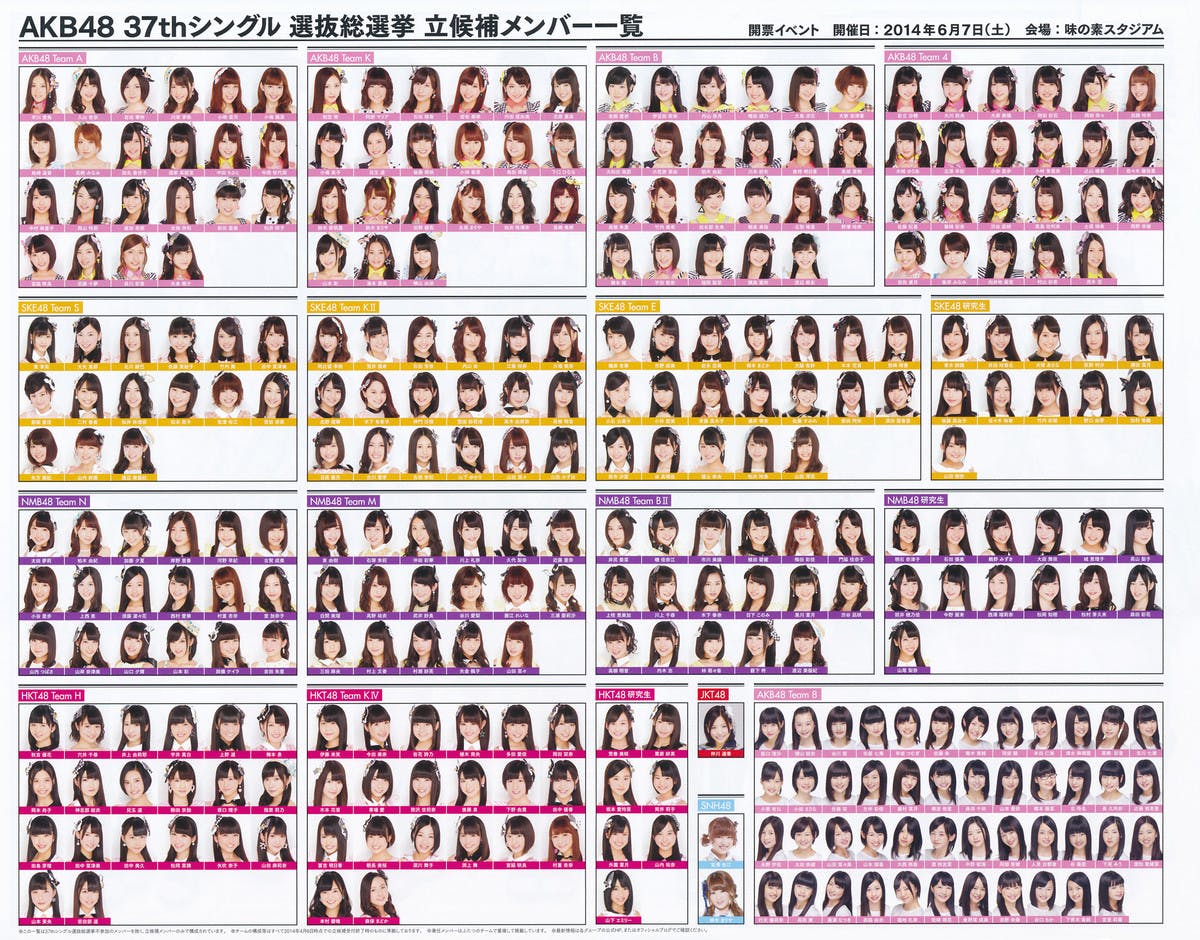

launching dozens of successful careers. One of the most popular Japanese idol-groups, AKB48 hosts more than 100 idols at

a time – and while some of the more successful members of the band are "graduating" to start their solo acts, the new

idols are recruited through numerous auditions all over Japan.

AKB48's full roster (37th iteration), split into teams.

The Industry of CD

There is yet another aspect of AKB48's business model, illustrative of the Japanese market. As the group is so big, all

of its members can't possibly be featured on the same song or even the same album. So, AKB48 holds a nationwide

televised election every year, allowing fans to decide who's going to be in the frontline of the band. Yet, there is a

catch: the right to vote is tied to the serial number of the group's latest "election single", creating an incentive

powerful enough to make some fans buy hundreds or even thousands of AKB48's CDs at a time. Needless to say, with the

average CD price across Japan at around $25, such techniques become extremely lucrative.

Adding value to CD offers to incentivize multiple purchases of the same piece of content is actually a widespread

practice in Japan. By far the most common way of engaging with the format is linking CDs’ serial numbers with a chance

to win a meet & greet session ticket. Yet, some of the artists choose a more inventive approach, like the K-pop

girl-band TWICE, who have included a range of photocards in their CD packages. As the owners of the full collection were

promised exclusive content access and tickets to meet & greet sessions, some fans made a full hobby out of trading and

collecting idol cards. Yet the bonuses weren’t the only reason for that – by tapping into collectibles culture, which is

very strong in Japan, TWICE added value to the CD offer and genuinely engaged the fan community, all at the same time.

The line for a handshake event with TWICE in Kobe, Japan, 2018

The Business of the Fan-Club

Another unique way to monetize fan engagement is linked to the "business of a fan-club". The fan-clubs are official

communities with dedicated websites filled with exclusive content. As the access to content is usually

subscription-based, such websites can generate a sizable amount of money, but, even more importantly, they allow fans to

find like-minded friends and organize their appreciation, dedicating both time and money to their favorite idols.

To put it in a context, the London-based fan-club of BTS pulled together a full-on outdoor marketing campaign to

celebrate the 5th anniversary of their favorite band: numerous billboards, featuring BTS were put up all over London

without a single penny invested by the group's label, making "UK ARMY" a part of a marketing team of the idol-band. The

fan-clubs would often turn into such crowdfunding communities for the idols – once again, without the latter ever asking

for it.

Billboard put up by BTS UK ARMY UNITE, South London, UK, 2018

The fan-club concept is probably the most globally spread business technique of the industry, as idols are now getting an organized following all over the globe. Meanwhile, some of the biggest international artists already noticed the potential of the strong fan community, promoting a new way of proactive and engaged artist-fan relationships, inspired by the idol fandoms. As Taylor Swift is now connecting with her fans with the help of a WhatsApp chat and showing up unannounced at the fan gatherings, it might not take long for the “business of the fan-club” to fully take root on the western markets.

Local Players Knowledge-Base

On that note, we'd like to conclude our analysis of the market by sharing a last piece of knowledge. While having strong positions on domestic markets, most Japanese music companies are almost unknown outside of the country. Therefore, in the final section of this article, we will introduce some of the must-know players on the Japanese market (in alphabetical order).

Avex Entertainment Inc /Avex Marketing Inc

There is a good chance you haven't heard of Avex, yet, Avex Group is the biggest local company in the entertainment industry, accounting for over $1,5 billion in sales and engaged in various areas of the entertainment industry. Avex remains primarily a music company: with over 30 local labels under its umbrella, affiliation with AWA and Line Music streaming services and a vast network of publishing and distribution deals, it is one the most influential and powerful companies on the market.

Creativeman Productions

Responsible for introducing Radiohead, Green Day and Beastie Boys to Japan, Creativeman Productions is one of the most prominent players on live promotion market. Creativeman works with international acts of various scope and organizes some of the tier-1 festivals around Japan like Sonic Mania, Summer Sonic and Greenroom Festivals.

Hostess Entertainment

If you're interested in exploring the possibilities of the Japanese market as an outsider, the one company you definitely should know is Hostess. Founded in 2000 by the British expat Andrew Lazonby, Hostess is one of the leading players in the 10% international niche of the market, seeking to represent international acts which got what it takes to make it in Japan, giving them more control over the marketing side compared to their major counterparts. Hostess now represents Beggars Group, Domino Records, V2 Records and PIAS in Japan, working with Adele, Radiohead, Arctic Monkeys, Mogwai, Bon Iver, Nine Inch Nails, Superorganism and alike.

JVC Kenwood Victor Entertainment Corp.

Founded in 1972, Victor Entertainment ranks fourth in the Japanese recording industry, surpassed only by Universal Music, Avex Group and Sony Music Entertainment Japan. Home to over 20 local labels and over 400 regular employees, Victor Entertainment can be considered a “local major” on a par with Avex Group – and it’s certainly a notable player on the market.

RecoChoku

RecoChoku is the leading digital music provider in Japan. It’s stakeholders are all the major labels (both global & local), as well as NTT DoCoMo, Japan's leading mobile phone operator, which also offers D-Hits – the most successful local streaming service in Japan at the moment. If you're curious to find out more about RecoChoku and the Japanese market in general — check out our interview with Goshi Manabe, RecoChoku's International Rep & Advisor.

SMASH

On a level with Creativeman, SMASH is another major local promoter on a Japanese market. Responsible for running the Fuji Rock Festival, which attracts more than 100,00 attendees, SMASH works with both local and major international acts from Kendrick Lamar and Post Malone to Aphex Twin and Bjork.

Tower Records Japan Inc.

Tower Records Japan was created in the 80s as a subsidiary of the legendary international retail franchise of the same

name, but went through the management buyout and became an independent entity in 2002, just four years before the

bankruptcy of its parent company. Now it is the biggest retail store chain in Japan, with more than 70 stores spread all

over the country, an online download-to-own distribution platform and over 400 full-time employees. As CDs still

dominate the Japanese market, POS marketing remains a very effective way of promoting music, and a partnership with

retail chains such as Tower Records can prove remarkably fruitful.

The companies mentioned above, however, represent just a fraction of the Japanese industry. To get a deeper view of the

local players, explore the following list: